Hei!

This week you have another post in English. First I want to share with you some background to a bit of research I did in 2015 on the value of our approach to producing food. It was written as an academic piece, with full references and I can forward these direct to anyone interested. The second part of this posting is Part 2 of the slideshow documenting the re-construction of the kasvihuone. Although it’s not totally finished, we now have it full with tomatoe plants and basil seedlings. Drop in some time and have a look!

Sustainable Food Systems and Community Supported Agriculture

The term 'sustainable food systems' is a reasonably apt description of the approach we in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) enterprise take to agriculture. From an environmental point of view, agroecology defines the dominant approach to such systems. This combines the practices of agriculture and ecology, seeking a multi-disciplinary approach to more sustainable food systems. It grew out of concerns with the expansion of industrial agriculture in the developing world and was originally concerned with the promotion of alternative production approaches, such as organics, biodynamics and permaculture (notes 1 and 2) (Silici, 2014). While the emphasis is on agricultural practices, there is a recognition that food systems will require more of a focus on social factors (Wezel and Soldat, 2009). Broadening the agenda of agroecology from environmental production practices to include an emphasis on marketing and consumption has led to a focus on food localisation. The idea of food being produced and consumed locally seems to have come to dominate much of the literature on sustainable food systems. It is peculiar that local food has come to be viewed as 'alternative' since, as Acherman-Leist (2013) points out, it is not so long ago that local food was the norm. It was only with the development of industrial agriculture in the last century and the globilisation of commerce that local production has been eroded. However, localisation has attracted a great deal of controversy. Much of this centers on fears of disguised protectionism and elitism (e.g. Hinrichs, 2003) and that it has been incorporated by the dominant economic system as another form of consumerism (e.g. DeLind, 2011). Perhaps a more useful angle on local sustainable food systems can be gained from the concept of civic agriculture. Coined by Lyson (2004), civic agriculture encompasses such practices as farmers markets, community gardens and CSA. It emphasises an holistic approach to achieve transformative change (Furman et al, 2014).

Finally, social change and sustainability are the platform of the increasingly popular food sovereignty movement. Food sovereignty derives from a re-examination of the right to food and to control food systems. It is therefore an inherently political concept, seeking to overturn 60 years of neo-liberal economic policy through societal transformation (Pimbert, 2009). Although it arose as a peasant-inspired movement, it has now been embraced by civil society organisations and academic epistemic communities also in the West (Hospes, 2014). This ideology could be viewed as underpinning CSA as a social movement and it certainly provides the basis for the activity of the international network promoting CSA, 'Urgenci' (see www.urgenci.net).

CSA responds to the creation of sustainable food systems by emphasising an holistic approach, within a local setting, with the potential to achieve transformative change. Among the various practices that seek to realise sustainable food systems, CSA is one of the most socially embedded (Obach and Tobin, 2014; Hinrichs, 2000) and should therefore offer great promise in terms of achieving local sustainability. The exact origins of CSA are debated, but the modern concept is generally recognised to have been popularised when a small group of European biodynamic farmers moved to the USA in the mid-1980's and helped establish the first farms based on the characteristics of shared responsibility and risk, community engagement and building the local food economy. The founders deliberately left the definition of CSA rather open so as to avoid the concept becoming too boxed in (McFadden, 2012). This no doubt encouraged the development of new initiatives but it has also made it difficult to be exact as to what is and what is not CSA. Lack of formal definition has also led to CSA being a contested concept (White, 2013) and some of the range of activity is more akin to food circles or group purchasing clubs ('ruokapiiri') than to community-based, shared, food systems. I hope in the course of this research to help clarify the breath of the concept and, in particular, which approaches are most supportive of sustainable community building.

Reasonable estimates for the number of CSA initiatives are for between 6000-12500 in the USA, about 4000 in Europe (mostly France) and perhaps 1000 elsewhere (the majority in Japan) (Kondoh, 2015; Lagane, 2015; Pole and Grey, 2013; McFadden, 2012; Urgenci, 2013). In Finland, the first CSA, a biodynamic consumer cooperative called 'Kaupunkinlaisten Oma Pelto' (www.ruokaosuuskunta.fi), was established in Helsinki in 2012. The lack of definitional clarity, however, is reflected in Finland where there are anything between 14 (Herttoniemi, 2015) and 64 (Vihanta, 2015) initiatives, depending on whether a Swedish-inspired food circle concept called 'REKO' is included or not.

The origins of the CSA concept bore a strong social renewal component and this derived in large part from values linked to biodynamic agriculture (White, 2013; Charles, 2012; Henderson and VanEn, 2007). Trauger Groh, one of the original biodynamic farmers involved in bringing the ideas to the USA, highlights the motivations as being: human health and wellbeing, fulfilling human needs and creating diversified and regenerative local communities (Groh and McFadden, 1997). These motivations are in turn identified by Groh as arising from the ideas of Rudolf Steiner in relation to social threefolding (see, for example, Steiner 1920, 2004):

spiritual/cultural freedom for individuals healthy development;

social equality in access to resources;

economic association/cooperation for the good of all.

Steiner (1861-1925) was an Austrian social reformer and philosopher who was active in a large number of areas including, education, agriculture, medicine and the arts. His ideas for social threefolding drew on the Enlightenment ideals of 'liberty, equality, fraternity' and sought to create an understanding for how different sectors relate to each other. These ideas are part of the holistic approach of biodynamic agriculture, shifting the emphasis away from simply producing food and towards more broadly social purposes. In light of this background, the integral values of CSA can be viewed as profoundly idealistic and progressive. It is also worth noting that they are not dissimilar to the traditional three pillars of sustainability, social, economic and environmental, particularly when the core activity of biodynamic agriculture is to directly enhance regenerative environmental carrying capacity (Wright, 2009).

While the broader 'community' aspects have been recognised as a crucial characteristic of CSA, indeed the very foundation of this approach to sustainable food systems, they have been most notable by their absence in practice. A number of studies have sought to explore why this is so (e.g. Pole and Grey, 2013; Henderson and VanEn, 2007; DeLind, 1999). The apparent trend is that as the approaches to CSA have expanded and become more popular, the tendency has been for a subscription-based model, with little community involvement desired or required, to replace the more challenging community-based approach. However, the reasons why this might come about and what can be done to maintain the broader social values requires further investigation.

1 Biodynamics is an holistic form of organic agriculture, originally developed by Rudolf Steiner

2 Permaculture seeks to model human and agricultural systems on natural ecosystems

The Kasvihuone rises!

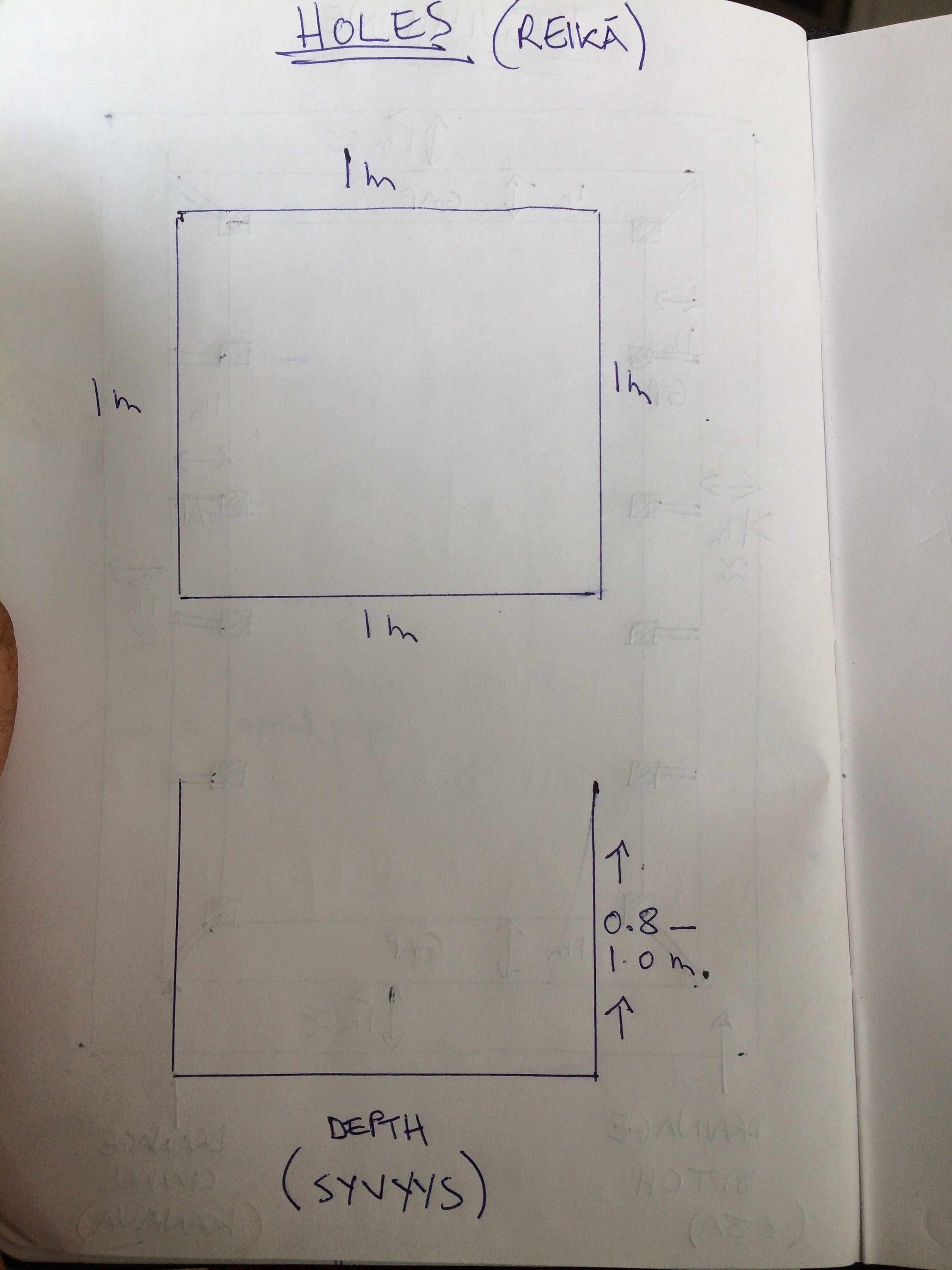

In Part 1, I showed us taking down and transporting the old kasvihuone from the other site. Having arrived at the main farm, the first job was to repair and paint the arches and beams, fix holes in the plastic and get the old frame ready to go back up. At the same time and when the weather allowed, we started planning and digging the foundations and new drainage channels. We are keen that the kasvihuone lasts a long time, so we paid particular attention to getting the base work done properly. Unfortunately this was slowed considerably by the weather, as the foundation filled up with water almost as soon as we had it dug.

Eventually, the weather improved and with a good deal of human and tractor effort we got the foundation laid and the pillars ready for the arches. Once the arches were all back up, we had to re-engineer the structure a bit to make it more stable. Then we were ready to put in the windows and put back on the plastic.

By this time we had already received delivery of about 150 tomato plants and we had to prepare the ground straight away to get them in. Because the building works has compacted the soil so much, making the new beds meant brining in lots of manure, peat, sand and chalk. Finally, last Monday morning, we planted the tomatoes.

Luckily, the weahter has been good to us and we can now take our time finishing the front and back of the kasvihuone. We are also just in the process of installing a watering system and tomorrow will hopefully get a wire grid made to act as support to the growing plants.

All in all, it was quite a project and we now have a great resource to grow specialist plants and to be able to get some things growing in early and late season. Many thanks to everyone who had a hand in the work!